Beaver, Shenango and New Kensington students visited a prison in Indiana to receive training for Bridges to Life, a restorative justice program they plan to implement in Beaver County this spring.

MONACA, Pa. — They sat in a loose circle in a high-security prison — victims, offenders, facilitators and several students from Penn State — and waited for the one named Christopher to tell his story.

Christopher’s fellow inmates encouraged him as he hung his head and fidgeted in his seat: You got this. We all have a story.

Finally, Christopher shook the memory loose. He was driving with his 2-year-old son in the back seat. He ran a stop sign. Another car T-boned him. He survived. His son did not. And because he had marijuana in his system, he ended up here.

A lot of tears followed the telling. A lot of supportive words. A lot of tissues.

Penn State Beaver student Dominic Rossi was floored.

“Holy (crap), this works,” he thought. “This can actually work.”

Rossi was talking about — and in the prison receiving training for — the restorative justice program Bridges to Life. Bridges began in 1998 when a Texas man, whose sister had been murdered, realized that the acceptance of responsibility could be a crucial piece of the healing process for both victims and offenders.

Bridges to Life is designed to trigger that acceptance by connecting communities and prisons. For 14 weeks, crime victims and volunteers go into prisons to talk with offenders about accountability and responsibility. Victims tell their stories and offenders complete curriculum-based worksheets and tasks. The result, according to two evidence-based research projects done on the program, is a dropping recidivism rate.

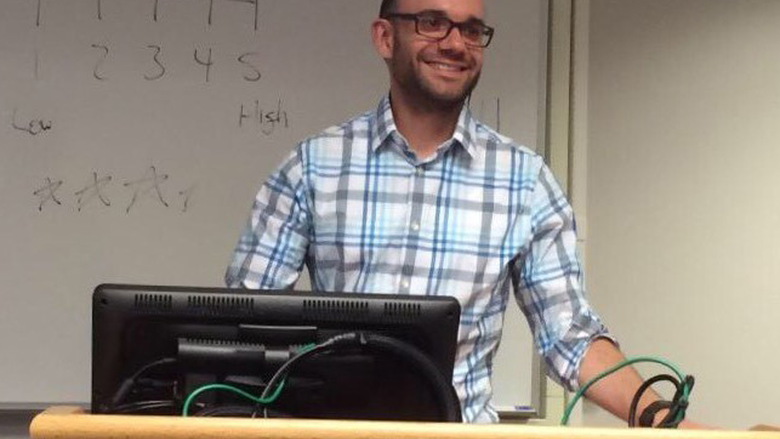

Penn State administration of justice instructor LaVarr McBride, having worked with Bridges to Life in other states, wanted his students to implement the Bridges program in Beaver County. So he applied for a $5,000 Schreyer Institute teaching project grant to take five psychology and administration of justice students to Indiana for Bridges to Life facilitator training.

He got it. So just before Halloween, Beaver students Rossi, Ashley Cutrona and Leigh Kilpatrick; Shenango student Paula Bucci; and New Kensington student Roya Fashandi got to see firsthand how Bridges works.

All five students had the same reaction to the experience, which Cutrona put into five simple words: “It was a game changer.”

It began with that evening in the high-security prison. Matt Morgan, a sexual abuse survivor and founder of the nonprofit Building Hope Today, spoke to the inmates, facilitators and students about his experience as a victim. Then the larger group broke out into several smaller segments. That’s where Christopher, and inmates like him, told their own stories. And it’s where the students, most of whom had never set foot in a prison or knowingly interacted with an offender, suddenly woke to a new understanding of inmates.

“They’re human beings, not the monsters the world thinks they are,” Rossi said. “They’ve been labeled, and we’re trying to reverse that.”

“They’re good people who did bad things,” Bucci added.

It’s exactly the message Bridges tries to impart to both the community and the offenders. But it’s often a steep climb. Society has been conditioned to mark offenders as bad and to confuse justice with retribution. Bridges views justice as something much more fluid, a feeling that can be earned and changed with understanding.

Kilpatrick felt that change intensely. She grew up believing in an “eye for an eye,” and she was nervous walking into a crowd of inmates. She was afraid they neither wanted her there nor took her seriously.

After the first breakout session, she shook the hand of an inmate who had just told his story and thanked him.

On the last stop of their training, in a lower-security prison, the students were given a tour by an inmate wearing a black suit. He talked about his kids and how he would see them in 22 days, when he would be released.

Kilpatrick went home and marked that day on her calendar. When it arrived, she smiled.

“It made me happy to think of him,” she said.

These are the moments and messages Kilpatrick, Rossi, Cutrona, Bucci and Fashandi will be charged with passing on to fellow students. As the inaugural cohort of Beaver County-based facilitators, they will not only go into the Beaver County Jail to work with inmates, but they will also be responsible for training future volunteers of the Bridges program and extending the reach of restorative justice.

“I hope people can open their hearts and minds to it,” Kilpatrick said. “It’s important for people to learn about it, because it works.”

April Johnston

Public Relations Director, Penn State Beaver